It all started 18 months ago with the completion of the MST400, a 7MHz SSB QRP transceiver in kit form. I’ve used this 40 meter 5 watt monobander for 34 SOTA activations to date. It is the radio that appears in every one of my activations in this blog till this weekend. Following the pleasing performance of the MST receiver I wanted to scratch-build an SA612 based radio, to see if I could reproduce the performance of the MST400 but with a few changes to make it even better for activations. I christened this radio the ‘Summit Prowler One’. Summit Prowler? Last year my First Harmonic and friends went through a huge ‘Magic The Gathering‘ stage. MTG is a mythical strategy card game full of weird characters with strange powers. When I first saw the MTG Summit Prowler card it occurred to me that there was a link to SOTA there, somewhere. First Harmonic has moved on to other games, but my first Summit Prowler has been born! Here it is, in its first incarnation, on the bench, around May 2016.

An SSB monobander for the summits

The design requirements were simple… reproduce (within reason) the overall performance of the MST400, keep the size and weight down, minimise current drain on receive, make it simple to build, align and maintain; and get some experience with the SA612 class of transceivers. There are lots of SA612 superhet designs around, and they all look quite similar after a while. Peter VK3YE has a minimal-parts transceiver, from which I stole the cunning superhet crystal mixing scheme. I took a side track and went looking for useful crystal frequency pairs for this superhet configuration. Being a Drew Diamond (VK3XU) fan I started with a lash-up of his Twin Crystal Filter rig on the basis that the separate receive and transmit strips would allow independent construction and alignment, simple T/R switching, without paying too much of an overhead in additional parts count and complexity.

One obvious question today for a superhet homebrewer is ‘To DDS or not to DDS’. The advantages need no explanation. While the 150 to 200mA current draw of a typical DDS was a consideration, the truth is that I have not scratch-built one yet, and I did not want this project to get stalled on the interesting but new challenge of learning AD9850/si5351 and Arduino, something I have collected the parts for but have not yet attempted. After watching dozens of VK3YE’s videos on minimal QRP I opted for a SuperVXO with a cheap Chinese eBay frequency counter as digital dial, as long as the swing covered the SOTA/portable segment of the band. Peter’s 8.867/16MHz scheme did just that, at the expense of coverage of what might be considered the phone segment of 40 meters.

The front panel is uncluttered with audio and microphone gain controls, an LCD frequency readout and an over-sized tuning knob. For tuning, my golden rule is that a big knob beats a smaller knob every time. A large knob makes tuning with the 10 turn potentiometer easy, even if it does look slightly over-scale for the rest of the panel. When I cut the rectangular hole for the counter I went too far, leaving an unsightly gap between LCD panel and the panel. So I squeezed in a rubber seal as a gap filler. It looks a bit messy, but does the job for now.

The rear panel has the usual fixtures, plus one. The ‘TX’ switch is a hard transmit switch, for CW, in the absence of any kind of electronic T/R switching and break-in. The ‘METERS’ switch is a 3 position toggle… in position 1 just the digital LCD dial is on (add 50mA); in position 3 the digital dial and voltmeter to the right are on (add 65mA); in position 2 both are off (receiver current draw is 45 to 50 mA). This is a simple battery-saving device, without having to sacrifice the convenience of a digital dial and voltmeter.

The heart of the transceiver is the VFO, in this case a varactor-tuned SuperVXO with two 16MHz crystals (in its own mini-box). With the 8.867MHz IF the tuning range is 7.078 to 7.112kHz. The varactor, lower left, is an MVAM109; series inductors are preformed RFCs, VXO and buffer are 2N2222s. A ten-turn potentiometer makes for about 3kHz per turn of the big knob which is plenty smooth enough.

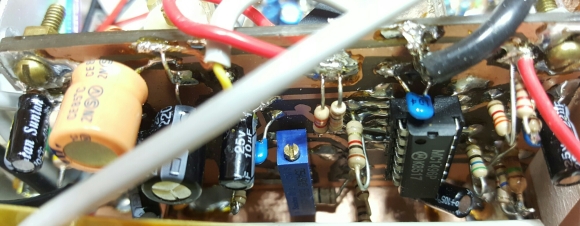

The receiver strip is closest to the edge of the chassis, from left, two tuned circuits in a bandpass filter, SA612 mixer, 4 pole crystal filter at 8.867MHz, SA612 product detector, and the audio stage from the MST400 Mark 2, an NE5534 audio bandpass filter and a TDA7052 audio amplifier stage. The 8.867MHz BFO is right-most, a 2N2222 with preformed RFCs to pull it off-center frequency, set experimentally.

The transmit strip (below) uses a TL072 mic amp (off picture to the left), SA602 balanced modulator, 4 pole 8.867MHz crystal filter (separate to that used in the receive strip), SA612 mixer, and the power amplifier comprised of a 2N2222 pre-driver, 2N3866 driver, and IRF510 final, for 5 watts on a 12 volt supply.

Close-up of the IRF510 with on-board heatsink.

So how did I go with meeting those design goals? Receiver performance was fair, not as sensitive as the MST400. The receiver drew <50mA with the meters turned off. The VXO was excellent, very stable, drifting minimally at switch on, perhaps a hundred hertz in the first few seconds. The 30kHz coverage was not wide enough but it was centered on the 7090-7100 QRP/portable window. Attempts to add a third crystal or more inductance gave more than 50kHz swing but became unstable. I’ve made the VXO in its own enclosure which could be replaced with a ceramic resonator-based oscillator or even a DDS module one day.

The transmitter worked but with some RF instability at full power. Some reworking of the layout and screening of the driver stages seemed necessary, although I have had several QSOs across town with this rig at this stage in its development.

Transmitter rebuild

The months rolled by, 2015 became 2016, summer faded to winter, during which Summit Prowler sat on the main shack bench, just off to the left, not central, but not forgotten, while other projects took centre stage. Have you noticed how the arrangement of your shack desk represents how you feel about your projects? Distance from centre-front is inversely proportional to your level of engagement. The chassis or PCB right in front of you is your main focus. Further back, left, right, and on shelves, things are not forgotten, just put aside. Things are really over when a project is relegated to a closed drawer or cardboard box. Line of sight to an object, or lack of it, has great significance in the workshop or shack. Maybe I should claim that thought… VK3HN’s Law of Homebrew Project Engagement.

The Summit Prowler receiver worked fine, although a little quiet for my liking. But I could not declare it summit-ready, as the transmitter was not tuning up properly, I could not get any decent RF power out of it, due to various instabilities. After a break, I decided to re-focus on Summit Prowler’s transmitter, rebuilding it as necessary until I had achieved good performance, as evidenced from a solid on-summit peformance.

Pre-driver and driver stages

First problem working backward from the antenna socket was oscillations in the PA. My casual layout of the transmit strip looked suspect. In the past, I have gone to great lengths to screen and even individually ‘box up’ successive RF stages. Not so this time. This was the first board layout I have made for a 3 stage RF power amplifier stage for about 20 years, and I had not paid ‘Mistress RF’ the careful attention she demands. The more I looked at the transmit PA, the more I realised it had to be rebuilt. So I stripped the pre-driver (2N2222), driver (2N3886) and rebuilt them in a sheilded box, without changing anything else about the circuit. The result looked like an RF fortress. Probably an over-correction. But the oscillations were greatly reduced.

Microphone amplifier, balanced modulator

When debugging serial devices like a transmitter, one problem often masks another. In trying to get a decent SSB signal drive for the partially rebuilt PA, I rediscovered that I could not null the carrier in the SA612 balanced modulator. I triple-checked my wiring and components. I tried multiple 602’s and 612’s with no improvement. I studied other NE602 circuits to see if Drew (VK3XU) had departed from conventional wisdom, but the TCF circuit was ‘best practice’. Then I read this comment …

From my experience NE612 (and also the old NE602) do not provide very good carrier rejection as a DSB modulator. The reason is one of the internal buffers that is not biased enough. As an RF mixer works well. I would recommend for DSB modulator the old MC1496. MC1496 can get up to 60dB carrier suppression when NE612 can get maximum 30dB.

The commenter linked to the venerable MC1496 datasheet to support his claim. I also found Bill (Soldersmoke), back in 2003, asking about poor carrier suppression on his NE602 balanced modulator in a 20 meter QRP DSB transceiver (‘sort of the same design used in the Wee-Willy rig’). He was referred to a similar circuit in Elecraft’s KSB2 rig. There is no post-mortem post so I don’t know how it worked out for Bill. But these and other discussions raised doubts in my mind, and the reference to the MC1496 brought back happy memories of using this 14-pin black caterpillar the late 1970s.

Checking my local supplier’s website, they’re in stock. So one night I pulled the components from the balanced modulator and microphone amplifier region of the TCF transmitter board, sketched out a replacement circuit using a TL071 and MC1496, drew up the board, and after two evenings, I had a replacement mic and modulator board, designed to be mounted vertically over the space left by the vacated components.

It worked first time, and the carrier null was convincing. To be clear, I have no basis to discredit the NE602 as a balanced modulator. It is highly likely that my board layout or inattention to a finer detail of the circuit, coupled with my general lack of ‘proper’ test equipment and my lack of engineering know-how accounts for the failure. There are times when I find the best way to move a stalled homebrew project forward is to scrap a module and build another one from scratch.

Transmit IF filter and transmit mixer

I was on a rebuilding roll. The decision to mount the mic and balanced modulator board on its edge was conscious — it meant I could make a second board for a replacement transmit crystal filter and transmit mixer, and mount the two back-to-back. This was my way of gaining extra board area and capitalising on empty cabinet space. I remade the transmit filter with 5 crystals (not 4) just for the experience, and because I now had room, and followed this with a new SA612 mixer.

Making boards that mount vertically instead of horizontally to save space is a good technique, as long as you make sure you have access to pads and components such as voltage test points, trim-caps and trim-pots. This is done by mounting these parts so that their adjustment shaft points upwards and is at the top (not the bottom) of the board. When you draw your own ‘artisan boards’ you can lay them out however you like.

The new transmit crystal filter and mixer also worked first time. At last, I had a clean, stable SSB drive signal at 7MHz. It took some time, but I was now fully confident in these two transmitter stages.

Putting it all together

After rebuilding most of the transmitter I was sure I was done. I connected the transmit mixer output to the PA input. There was 7MHz RF at the output, but things at the IRF510 still weren’t right. Turning the bias trimpot to increase power gain, the power supply ammeter increased markedly at one point (up to an amp, or 12 watts input power), the device got hot, and the SWR/power meter went off scale regardless of mic input. After hours of probing, I began to suspect the purity of the 7MHz signal at the output of the transmit mixer. As a test, I soldered a 7.125MHz crystal onto a generic oscillator/buffer board retrieved from the junk box and, using this as a source of clean RF drive, the power amp came good, I got a few watts of carrier without the PA behaviour as before.

I wondered if there may have been 8.867MHz BFO energy getting through the transmit mixer into the PA. Not having a spectrum analyser, but knowing that well-designed QRP rigs use BPF filtering between transmit mixer and the PA to clean up the signal before it is amplified, I decided to try a BPF.

7MHz BPF and gain stage

Next, I built a 40m BPF from the kitsandparts design. I added a one transistor (2N3904) post-filter gain stage. My first attempt at the 2N3904 stage used a tuned toriod in the collector and it oscillated wildly. I replaced it with a 1mH RFC and it settled down. The BPF tuned up really well and was quite sharp. I tested it by monitoring the BPF output on a non-resonant wire with the general coverage IC746PRO, tuning from about 6 to 7.8MHz gave a big noise peak at 7.1MHz, and at 7.5MHz even the broadcast stations were well down. I put the filter/amp in front of the TCF receiver and it suddenly became much more lively!

To avoid overload on big signals I dropped the 2N3904 supply from 12v down to about 6v and the gain dropped to a nice level. I then added a tiny surface mount Omron DPDT relay at either end of the BPF module (with the poles paralleled to minimise contact resistance) to switch it between transmit and receive.

On air

With the partially rebuilt Summit Prowler One on the bench, I started making QSOs with success. Metered power output was less than that from the MST400, which uses essentially the same PA stage, I guessed it to be around 5 watts. On air, I got good reports, just as you would expect to get with about 5 watts of SSB on 40 meters to a dipole. Here’s a tour of the rig’s internals.

Satisfied that I had ironed out the last bug, I made plans to take Summit Prowler One to a summit.

And on a summit

Sunday 23rd October was the day for a maiden activation. I headed out to Warburton, about 90 minutes north east of Melbourne for Mt Little Joe VK3/VN-027. I took the MST400 in the pack as a backup, although I thought Summit Prowler One would work fine.

After setting up the inverted vee on the squid pole and both transceivers, receive audio level was low on both. I know that SOTA summits are meant to be low noise but this seemed odd. Now 40 meters in VK in the middle of the day has not been good of late, in fact most SOTA activators have started to routinely work multiband and multimode to maximise their reach. But after dropping the squid pole I found the solder lug that connects the braid end of the dipole to the SO239 flange floating in the air. The small nut and bolt must have worked free.

After setting up the inverted vee on the squid pole and both transceivers, receive audio level was low on both. I know that SOTA summits are meant to be low noise but this seemed odd. Now 40 meters in VK in the middle of the day has not been good of late, in fact most SOTA activators have started to routinely work multiband and multimode to maximise their reach. But after dropping the squid pole I found the solder lug that connects the braid end of the dipole to the SO239 flange floating in the air. The small nut and bolt must have worked free.

With that fixed, and a spot up on Sotawatch, the activation commenced, and went well, the Summit Prowler offering good receive performance on the mountaintop, plenty of gain, and acceptable signal reports from VK2s and VK5s. I then moved on to Mt Strickland, VK3/VN-030, about an hour’s drive north, and just south of Marysville. Here, in the later afternoon sun, conditions were excellent, both in terms of the environment and propagation. Here’s a sample of how it sounded:

So after a complete rebuild of the transmitter I declare Summit Prowler One done! There’s a write up of the two activations with more detail and pictures in another post.

Post-build reflection

This is the first time I have attempted a full scratch-built HF SSB transceiver for over 20 years, and I have had to re-learn a few forgotten lessons. Here’s a few reflections on the build:

- RF is a harsh mistress, like the Sea, she can be alluringly calm, but turn wild in a moment. I layed out some areas of my transmitter board as if for DC or audio, and an RF storm erupted. It took a total rebuild to tame her.

- When you step off a well-trod path you pick up burrs in your socks. Leon’s MST400 is a mature kit. Hundreds have been built and have worked first time. Mine worked first time and had never stopped working. Alignment was a breeze. But when you a) lay out your own PCBs, b) change components, c) design your own physical layout, or d) interchange modules, you change the original design, and as far as the designer is concerned, all bets are off. This is the difference between kit-building and scratch building.

- If you are not Drew Diamond (VK3XU), Wayne Burdick (N6KR) or other legendary RF designer, persistence is an essential characteristic for the scratch-builder, because the inevitable problems will derail you without it. But scratch building is fun and so rewarding when it works.

- I don’t have any decent test equipment. A good oscilloscope and spectrum analyser, paired with sufficient familiarity to get the best out of them, would have shaved a lot of hours off this project.

- Every failure teaches you something, if you persist. I remember now what I learned when I was younger about the importance of a ground plane, shielding, and decoupling. I learned about RF amplifier gain, the distribution of gain along a receiver or transmitter, about the need and place for BPFs to clean up after a mixer, and about amplifying after filtering. I learned about taming a power amplifier. And about how far you can pull crystals. And about the trade-offs between your choice of VFO/VXO and IF for a given signal frequency. And other things I can’t even remember right now.

One thing’s for sure. The next one I build will be so much better/faster/more efficient.

Dom (M1KTA) asks whether the KX1/HB-1A are in fact clones of Drew Diamond’s TCF. He blogged in 2009 that the circuit is dated 1994 which predates the other two (by Elecraft and by BD4RG) by more than 10 years. There were so many NE602/LM386 designs around it is not surprising that similar designs appeared. Hats off to Drew for publishing the design so early on.

Thanks for your comments Dave. Now that this project is done, I have bench room for that SST on 30m we were chatting about. I’ll follow your commentary re mods. 73.

LikeLike

It looks and sounds great Paul. Much more rewarding than if you’d simply taken an FT-817 up there. Thank you for sharing photos and details of this little rig – it helps to keep the art of “rolling your own” alive!

Dave

AA7EE

LikeLike

Great job there Paul! Looks like you have been on a rewarding home brew journey!

LikeLike

Hi Glenn, it was a journey with this rig, stretching over about 18 months. I think you have more success with your summit radio projects from what I read. At least I dont think you do very many complete transmitter rebuilds! 73.

LikeLike

It’s very satisfying to be on a summit using a radio that you have built yourself though! Kind of makes all the stress and bother worthwhile.

Talking of rebuilds, currently rebuilding the filter section of a 3 year old HB amplifier.

LikeLike

[…] La suite, en anglais, sur le site de Paul, VK3HN […]

LikeLike

[…] secondly, having finally finished the Summit Prowler One (a 40m SSB scratch-built VXO-based transceiver) I wanted to experiment further with simple […]

LikeLike

[…] secondly, having finally finished the Summit Prowler One (a 40m SSB scratch-built VXO-based transceiver) I wanted to experiment further with simple […]

LikeLike

I would love to see the schematic although I understand it is a pretty standard circuit. Even a hand drawn sketch would do, I volunteer to translate it to computer drawing format. TIA.

Greetings from an overcast Spain EA5 (at least today…)

Juanjo, EC5ACA

LikeLike

Hola Juanjo, yours is the second request this week for a circuit. I will get onto it! Thanks for your interest. Adios es 73 de Paul VK3HN.

LikeLike

[…] rigs, affectionately known as ‘summit prowlers’. I started with a 40m SSB monobander (Summit Prowler I), next a Wilderness SST for 30m CW (Summit Prowler II), followed by a 160m AM/CW transceiver […]

LikeLike